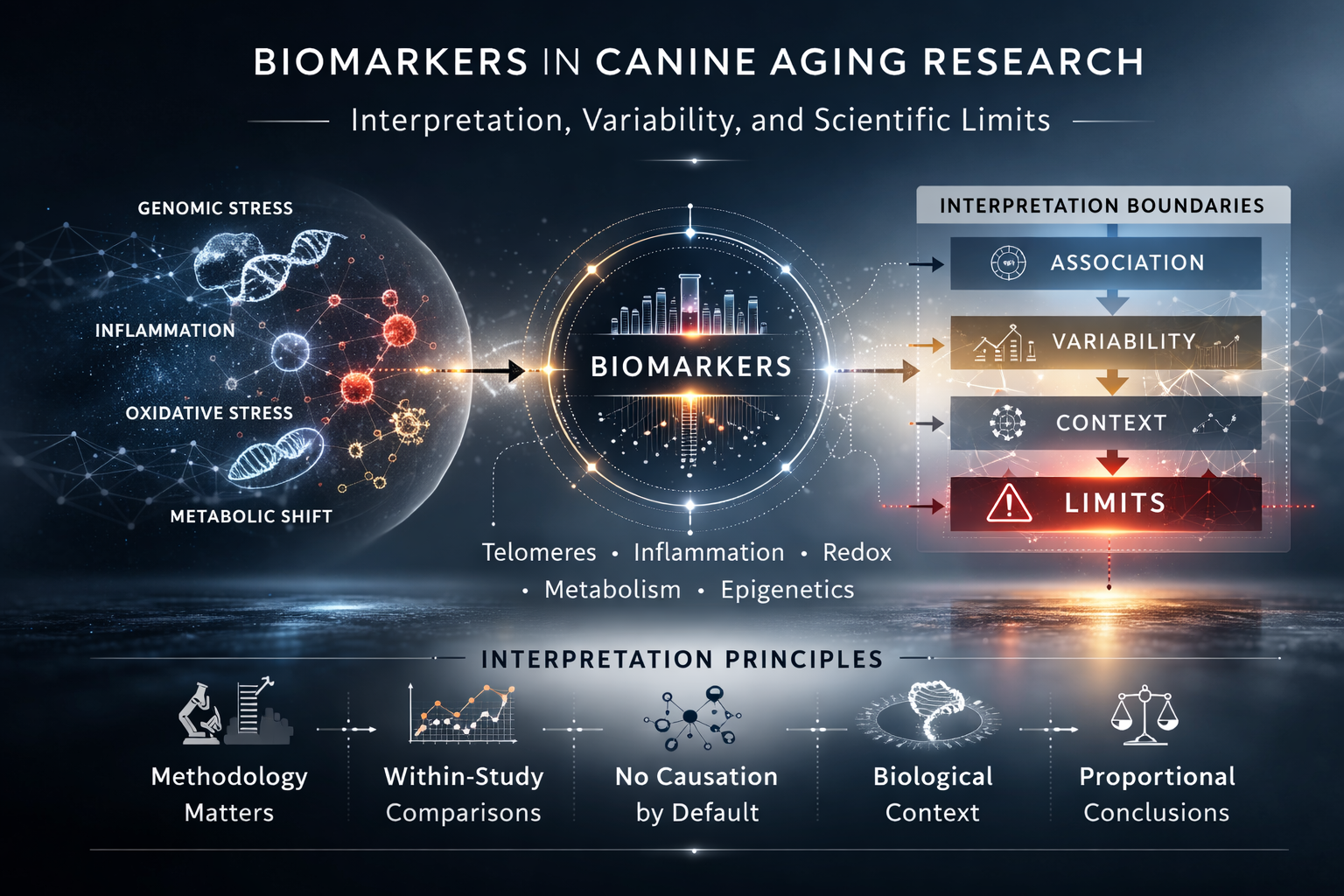

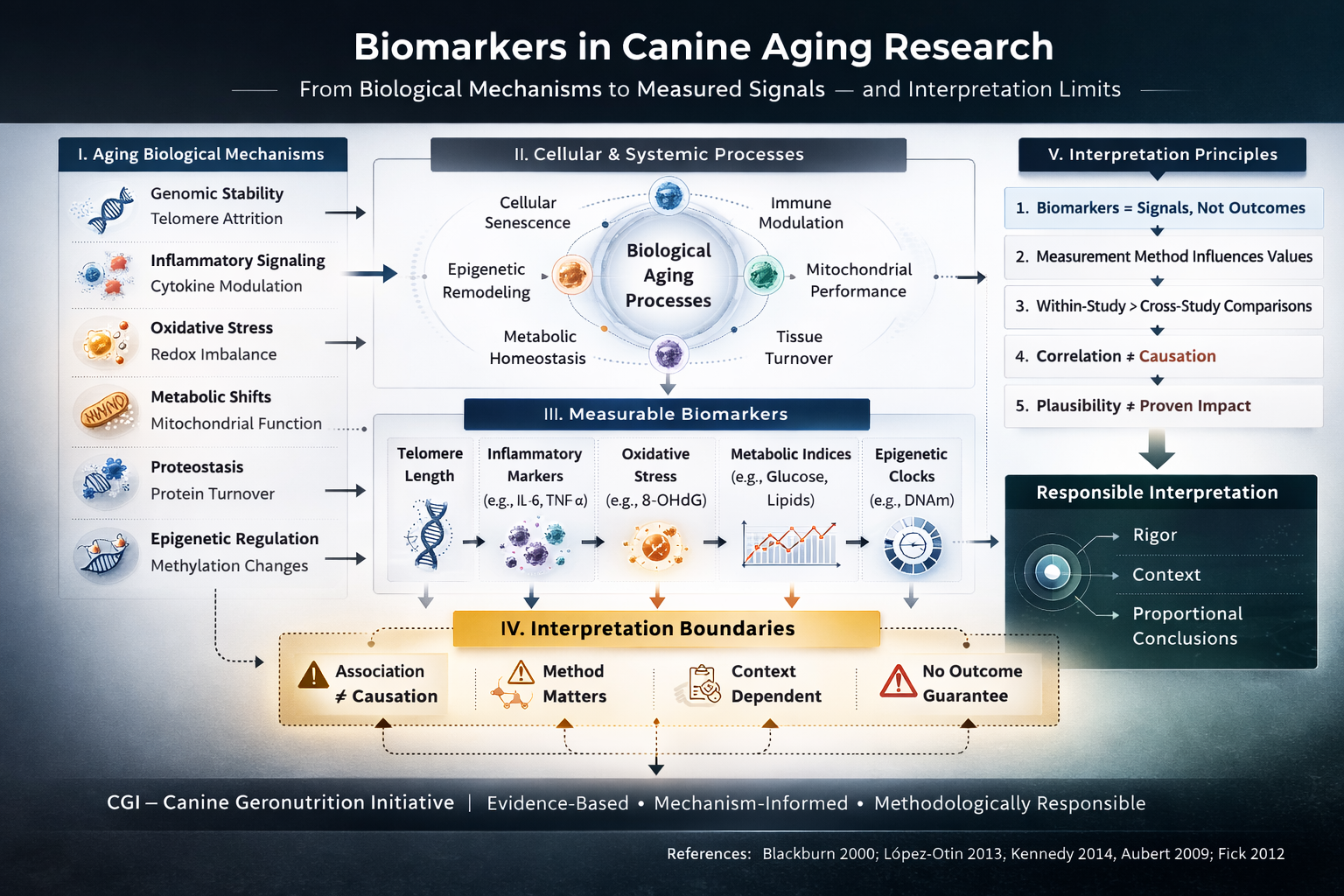

Biomarkers in Canine Aging Research: Interpretation, Variability, and Limits

Biomarkers play an increasingly visible role in aging research. In companion animals, measurable biological parameters such as telomere length, inflammatory markers, metabolic indices, and epigenetic signatures are often discussed as indicators of age-associated processes.

However, the presence of a measurable signal does not, by itself, establish clinical relevance or lifespan impact. Responsible interpretation of biomarker data requires careful attention to methodology, biological context, and study design.

This article outlines key considerations for understanding biomarkers within canine aging research.

1. What Is a Biomarker?

A biomarker is a measurable biological parameter that reflects a physiological or biochemical process. In aging research, biomarkers are used to characterize patterns associated with cellular or systemic change over time.

Importantly, biomarkers:

-

A change in a biomarker indicates a measurable shift under specific experimental conditions. It does not automatically imply disease prevention, functional improvement, or extended lifespan.

2. Categories of Biomarkers in Canine Aging

Aging research in companion animals may evaluate several classes of biomarkers:

Each category captures a different dimension of biological activity. No single biomarker fully represents the complexity of aging.

3. Association Does Not Equal Causation

One of the central interpretive challenges in aging research is distinguishing association from causation.

A biomarker may correlate with chronological age or physiological status. However:

-

many cases, biomarkers function as signals rather than determinants. They reflect ongoing processes but are not themselves sufficient evidence of intervention efficacy.

4. Sources of Variability

Biomarker interpretation must account for multiple sources of variability:

For these reasons, biomarker values are most meaningfully interpreted within-study and within-method contexts.

5. Study Design and Endpoint Context

Interpretation depends on how the study was structured.

Understanding the design clarifies the weight that can reasonably be assigned to findings.

6. Interpretation Principles

Within the Canine Geronutrition Initiative framework, the following principles guide biomarker interpretation:

-

These principles aim to preserve scientific rigor and prevent over-extrapolation.

7. Integrating Biomarkers into Aging Dialogue

Aging is a multifactorial biological process involving genomic stability, mitochondrial function, proteostasis, immune modulation, and metabolic coordination. Biomarkers offer windows into these systems, but no single metric captures the entirety of biological aging.

Responsible geroscience requires:

-

Advancing canine aging research depends not only on collecting data, but on contextualizing it appropriately.

Conclusion

Biomarkers are valuable tools in aging research when interpreted proportionally to study design and methodological constraints. In companion animals, measurable parameters provide insight into cellular and systemic processes, yet they do not independently establish lifespan extension, disease prevention, or therapeutic efficacy.

Scientific progress in canine geroscience depends on disciplined interpretation as much as on measurement itself. Clarity in this distinction preserves both credibility and rigor.

Suggested References

Findings discussed on this platform reflect interpretations within controlled experimental contexts and should not be extrapolated to clinical or lifespan outcomes without further evidence.